“Reaping with Joy”: IOCS at 25

The Very Revd Dr John Jillions is one of the founders and the first Principal of IOCS (1997-2003). He now serves as a Visiting Professor and a member of the Board of Directors. He has degrees from McGill University (BA), St Vladimir’s Seminary (MDiv, DMin), and Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (PhD). From 2003 to 2012 he taught at the Sheptytsky Institute for Eastern Christian Studies, Saint Paul University, and the University of Ottawa. Subsequently he was Chancellor of the Orthodox Church in America (2011-2018), taught at St Vladimir’s Seminary as Associate Professor of Religion and Culture, and as an adjunct at Fordham University. He is the author of Divine Guidance: Lessons for Today from the World of Early Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2020). Fr John has been a priest for forty years, serving communities in Australia, Greece, England, Canada, and the US. He is Vice-President of the Orthodox Theological Society in America.

33

Friday, October 22, 1999

We’ve had the Institute’s first study weekend (October 15-17, 1999), led by Fr John Breck teaching on the New Testament. 40+ students! Happy and successful. Friday-Sunday, five lectures (in Wesley House hall). Vespers on Saturday evening and Liturgy on Sunday morning at St Peter’s—the tiny stone church built in 1087, only a few years after the Great Schism. But the only time I have these days for writing in my journal is on the train and plane. It’s just before 8 pm on the train from Paddington to Oxford for the Sourozh clergy meeting overnight. I didn’t leave Cambridge until 6 pm. All of us at the Institute worked hard all day to get everything ready: the minutes, agenda, and financial report for the Working Group meeting on Monday. A letter to all the students who came to the first study weekend. Another letter to each Orthodox parish in the UK asking for support of the “challenge grant” set up by our generous “anonymous donor.” And I was also steaming through the paperwork buildup of the last two weeks.

It’s such an indispensable help to have competent people working for the Institute. I was happy to have Samantha Goode helping with the library, bookstore, and other projects. We put up the large icon poster in the office today. The mood is still effervescent and satisfying, with Deni coming in with cups of coffee and jelly donuts. So much has been happening. A trip to Lincoln on Wednesday to pick up books for our infant library from the late Canon Peter Hammond’s collection. Yesterday I led my first New Testament Seminar for the Cambridge Theological Federation (on Galatians 3:1-14).

But I haven’t seen a lot of our boys except for getting home late and watching TV with them. Daily vespers have been restful in these busy days, but in the mornings it’s only fitfully that I find (make?) time for quiet, reading, and praying. Fr John Breck warned me that prayer “is the first thing to go.” We had an important conversation the morning he left to return to Paris. His advice on how to keep the Institute sane:

- Pray.

- Take time off each week: Sunday afternoons and another day completely away.

- Schedule time with the children, with Deni (include weekends or days away at the monastery of St John the Baptist or elsewhere)

- Summers: take time—“sacred, and away”

He said that one of his saddest moments of his academic career was at the start of his second year of seminary teaching. He met one of the longtime faculty walking down the driveway coming toward him and looking downcast, just having returned from summer vacation. Fr John gave him a big hug, but his colleague shook his head and said, “Here we go again.” The next nine months were just to be gotten through until next summer. Fr John said that if I don’t insist on a better balance now—and insist on it for everyone—then we’ll all end up like this and the Institute’s mood will be awful. Chris Hancock (vicar of Holy Trinity, Cambridge) had similar things to say when we met for lunch on Tuesday.

- He’s learned to cut out any meeting that doesn’t add value to his work and life

- 2-3 days times a year he take a couple days to plan, to get control of your life rather than allow it to pull you in every direction

- Be part of a support group

- Any free time he finds unexpectedly he uses to schedule something enjoyable with his wife (dinner, movie, etc.)

The study weekend was very successful, but I was still anxious. I felt the weight and fear of the demands (real and imagined) of our new students, many of whom want and need direction in their work and lives. A part of me just wanted to pack up and go home. Help, Lord. Keep me “in the springing of the year.” It’s an amazing life we’ve been thrown into. Even the money is trickling in.

A Prayer in Spring

Robert Frost

Oh, give us pleasure in the flowers to-day;

And give us not to think so far away

As the uncertain harvest; keep us here

All simply in the springing of the year.

Oh, give us pleasure in the orchard white,

Like nothing else by day, like ghosts by night;

And make us happy in the happy bees,

The swarm dilating round the perfect trees.

And make us happy in the darting bird

That suddenly above the bees is heard,

The meteor that thrusts in with needle bill,

And off a blossom in mid air stands still.

For this is love and nothing else is love,

The which it is reserved for God above

To sanctify to what far ends He will,

But which it only needs that we fulfil.

32

Tuesday, September 28, 1999

Yesterday afternoon Bp Basil called to say that the Directors had agreed to hire Denise as the “development consultant.” Seraphim Alton-Honeywell (legal counsel) had some reservations about not publicizing the job, but Bishop Basil, Bishop Kallistos, Graham Dixon, and Howard Fitzpatrick felt this was unnecessary given the Institute’s meagre finances. So, we are both employed by the Institute. All our eggs are in this one basket. Help Lord!

Today we move from our temporary office to the new quarters on the other side of Wesley House. Yesterday our newly hired administrator, Graham Howard, had his first day. Mother Joanna has been here just two weeks to assist with students and the study weekends. Fr Nicholas Loudovikos and his family arrive next week. The phone lines and cable for the computer system goes in today. Desks arrived from Office World. Three new computers are coming this week. Dave Goode has been invaluable with this setting up, and Samantha too. They patiently and cheerfully painted the whole place. The money is trickling in, but we had a big boost last Friday with 5,000 pounds from one of Fr Samir’s parishioners at the Antiochian church in London. Meanwhile, Alex and Andrew are home with the flu. Anthony has his first football match today. And Deni finally gets to put in her notice at Tyndale House. They’ve been very good to us. From the epistle today: “Give thanks always and for everything…” (Eph 5:20).

Wednesday, September 29, 1999

A few moments of quiet sitting in the new seminar room at our Wesley House premises. Graham has just left. Mother Joanna came in for a few minutes and has now gone to her first meeting for CTF international students (we have three doing the MA). Graham and I spent the morning finishing off the move from the temporary office and pulling up carpets to reveal the wooden floors. Boxes and computers everywhere. The phone lines are in, and Dave will be coming by this afternoon to finish installing the computer cables. He worked here late last night on the office and didn’t get home until 1:30 am.

With Mother Joanna, Sr Makaria, Dave and Sam Goode we had a memorable dinner at Howard and Laurie’s. They leave tomorrow for a new life in Venice, and I’m really going to miss the daily give and take with Howard as we worked together setting up the Institute this past year.

Anthony had a good football match yesterday as goalie. He only let one goal in, and that one was high into the corner of the net. He’s not afraid of going after the ball or knocking someone over. Alex is still home with the flu. Andrew went back to school today.

Monday, October 11, 1999

On the train from London to Cambridge. Just finished a morning at Premier Radio for a live interview (9:30-10:00) with John Pantry (a musician and C of E priest), a live phone call-in, followed by an interview with John Buckridge, editor of Christianity. But the day there began with a “chance” elevator meeting with Peter Kerridge, the station’s managing director, who studied patristics at Oxford with Bishop Kallistos and has long wanted to get the Orthodox into mainstream radio and their internet project “On Prayer.” He will arrange a meeting to see how the Orthodox could be involved. He led a quick staff meeting before the interview began on air and asked me to pray. I used “O heavenly king” and St Philaret’s prayer for the start of the day (“Lord, grant that we may greet the coming day in peace”), as often happens people were moved by these simple words from the Orthodox tradition. Once again, open doors.

The last few days have been amazing. Howard and Laurie are gone but the Institute is moving forward. Deni finished working at Tyndale House (Bishop Basil and Bishop Kallistos gave her the go-ahead), the computers are in, the bookshelves were built on Saturday by Andrew and Dave (and his friend Mike). Samantha is varnishing. Yesterday—Sunday—the offices were humming with conversation as we came through the offices for coffee hour after the St Ephraim’s parish liturgy with the 30 people who were there. Last week Bishop Basil and Fr Gregory Woolfenden came up from Oxford for the opening of CTF worship followed by a reception. There was a farewell to Joy Tetley and a welcome to the new Orthodox Institute. Zoe Bennet Moore gave us a very warm welcome and Bishop Basil gave just the right response, grateful to the CTF for getting us off the ground.

I’ve had an education in media lately. Today there’s an interview on the BBC’s Cambridge affiliate. Tomorrow a phone interview. And our press release was sent all over the world.

The first study weekend is quickly approaching. There’s still too much to do and I need to stay focused. But I also need to remember I’m human. Went to hit some golf balls with Andrew last night. Friday night I played squash with Anthony. I was happy to see Alex walk over to the Institute after basketball tryouts at the Leys. I love to see the boys relaxed at the Institute and—I think—proud of what’s being done.

31

Monday, August 30, 1999

Tired. On the way to Oxford to meet Bishop Basil and Bishop Kallistos after getting off the all-night plane from Newark to Gatwick. George and Elizabeth Theokritoff drove me to Newark Airport and along the way we talked about the OCA’s All-American Council [July 25-30. I was there with Stewart Armour and Fr John Breck. Bishop Kallistos was the keynote speaker—he made a quick plug for the Institute—and we made a presentation at one of the Council’s side-sessions.] We also spoke about my trip to Wichita to see Bishop Basil Essey, Eric Namee, and the Farah Foundation, and funding proposals, including the idea of Denise potentially being hired as a development consultant. Bishop Basil, Fr Anthony Scott, and Eric Namee all agree that no project like this can thrive long-term without having someone focused on development.

I got to Oxford just after 11 am and Bishop Basil came to the door in a crumpled white shirt with grass stains on his back. He’d been resting on the lawn in the garden after picking plums. It’s always restful to see him, especially when I’m feeling so perpetually pressured and rushed. He shooed the cat off the table, and we sat down for tea to catch up, though he was interrupted now and then by phone calls. On one longer call he had to leave the room, so I walked out into the old and peaceful garden. I can see such care devoted to it. I brought him up to date on everything and broached the idea of hiring Deni as a development consultant. We went over the points to discuss with Bishop Kallistos. It’s a genuine pleasure and privilege to work with him so closely. He too likes this joint effort and reminded me of what I’d told him a couple years ago after attending the conference in Villemov about lay academies: “It was all started by one person and a bishop.” He thought we should hold on to the Working Group as long as possible, until we are certain of the right Board.

Glorious weather. The door was open at 15 Staverton Road. Bishop Basil knocked, Bishop Kallistos came to the door in good humor and ushered us inside just as Rebecca White, the Warden of St Gregory and Macrina House (and one of his students) was getting up to go. I’d never been in his study before, but it was exactly as I’d imagined. Walls covered in bookshelves. Extra tables piled high with more books and manuscripts. Two large armchairs, well worn. A couple of little coffee tables. (He brought in tea and ginger snaps). A desk facing the garden with a tilted writing board. Pictures here and there. I noticed one lying on its side, of Fr Pavel Florensky. A very modern ergonomic desk chair. He brought another armchair from the next room. What a pleasant afternoon, a combination of the main business—they were interviewing me to finalize the Principal position—and talking about various issues concerning the Institute.

Bishop Kallistos had looked at my CV and said there were a few pleasant surprises. He didn’t realize Denise was of Greek background, and this put her in a new light. He asked about the Doctor of Ministry I had started at St Vladimir’s Seminary and was pleased to know it could be completed and I would then have two doctorates. He asked me to fill in a few gaps: where I was born and when, the ages of my boys, but otherwise he seemed quite satisfied, and noted that I’d had financial and management experience. He reiterated the importance of the CTF’s approval for my teaching and thought this was obviously important. We then went over the job description for the Principal’s position. He wanted to see the academic responsibilities placed first, keeping in mind that IOCS is a college. The description should reflect the post not just as it is now but as it will become. Though Bishop Basil sees that for now reality dictates that management and strategic planning must be at the forefront.

I asked Bishop Kallistos about the possibility of a trip to the Phanar to seek the blessing and support of the Ecumenical Patriarch. Bishop Kallistos had already been thinking about this and will ask Archbishop Gregorios to let him do this, perhaps in early October. Bishop Basil and I emphasized to him that he is the only one who can pull this off, and he knows this too. As he said, “We may need to be like the importunate widow and keep pressing.”

Bishop Kallistos’s next appointment had arrived. We took some pictures in the garden (which was also immaculate). One of each, both the bishops, and the three of us, taken by the parishioner who’d come to see him. We took our leave of the very happy afternoon, and Bishop Basil drove me to the train station.

30

Wednesday, June 30, 1999. The synaxis of the Apostles.

Sitting in my little temporary office I’ve been given in Wesley House, on the Jesus Lane side of the campus, I am much relieved that my interview by the CTF Faculty Committee is over. I was worried, but it was very genial. I still need to submit a reference (they suggested Bruce Winter). A few minutes after the interview was over John Proctor announced, “It’s white smoke!”

During the interview John, Janet Henderson, Graham Davies, and Eamon Duffy each took a turn asking questions. I had mental images of my failed SVS Faculty Seminar three years ago as I walked in—and was asking God to block them out—but in the end it was all quite relaxed. They weren’t being too picky, and were instead seeking to find a broadbasis to welcome me in. John Proctor asked how I might handle teaching New Testament, the Synoptics in particular, given western scholarly interest in historical context and where the text comes from. For me, while it’s an issue, it’s secondary to the theological meaning and importance of the text. I told him my stress would be on the unity and diversity within the New Testament. He told me later that they assume students know the text well but that they don’t know the context or the historical issues. One needs to be prepared to handle questions put to the text.

Janet Henderson was interested in how I would approach liturgy, the influence of Alexander Schmemann, and supervising students who came from a “free liturgy” school of thought. Graham Davies was interested in my training, how I got from parish priest to New Testament scholar, and my level of Greek (John Proctor also asked about the teaching of Greek at SVS). He asked about my review essay in the St Vladimir’s Quarterly on the text of the New Testament, about the sources for my dissertation, and who was supervising me here in Cambridge. Eamon Duffy wanted to know how Orthodox students would fit into the setup in Cambridge. I felt that the example of the Institute’s staff would be key here, by insisting that student essays take into consideration other points of view.

I was anxious, of course, before I went in. Just beforehand I’d seen Eamon Duffy walking up the stairs. He smiled and said, “You must be sweating profusely! I have another one of these at 10:15, so I’ll have blood on my hands all morning.” When it was over I went out to get a cappuccino and a French pastry to celebrate the end of this, and when I returned John Proctor was coming in. The committee (and I) recognize that I’ll have great responsibility for the Institute as it gets set up, but gradually more teaching could be added. I admitted in the interview that I had little teaching experience, and they knew that could be addressed. But it was clear that they were willing to work with me and saw this as a process.

***

It has been incredibly busy, and much I should have written about at length I can only note:

- Developments with the Center for Advanced Religious and Theological Studies [CARTS], detailed meeting with Prof David Thompson yesterday and links with the Cambridge University Development Office

- Preaching at London Cathedral

- Deni, Alex and Anthony were at the Sourozh choir conference

- Faux pas with Archbishop Gregorios. I was inspired to write directly to Patriarch Bartholomew about blessing the Institute. But protocol dictates that I should have talked to the archbishop first and gone through him. Perils of divine guidance!

- In the middle of all this Andrew finished his GCSEs, started work experience at Lloyd’s Bank, and is going to Greece for two weeks with his friends Matt, Dmitri, and Rupert on Friday (to Katerini, where Dmitri’s family has a flat).

I’ve tried to squeeze in a few days of academic work but only managed a half-day—an afternoon when Fr Stephen and Lois Plumlee were visiting. That morning, I spent two hours with Andrew helping him prepare for his Divinity GCSE. I’ve been working from 6:30 am to 10 pm every day lately, and still the demands from other people and for articles etc. keep piling up. Howard has been great, and I will sadly miss him when he and Laurie move to Venice. Brochures, courses, budget, fundraising, the Working Group meeting, and reception coming up on July 15th. God help me. Now I’m off to the station to meet Tim Grass (Evangelical Alliance) and to go over his paper on “Evangelical and Orthodox Spirituality.”

Friday, July 16, 1999

The big meeting and reception marking the official beginning of IOCS was yesterday. I’m sitting in the office at Wesley House. It’s a complete wreck. Boxes of wineglasses and IOCS mugs, brochures (20,000 of them?), big plastic bags with Mother Joanna’s curtains for her office, and on one desk a stack of dirty serving plates. On another desk the remains of yesterday’s legal proceedings: the bound copies of the “Memorandum and Articles of Association,” the official letter of incorporation and the charter of registration (both framed), and the official corporate seal. Coffee cups, the icon of St Vladimir (July 15th), the hum of the computer, the flashing answering machine. I finished-off the last prosphora from yesterday’s liturgy.

It was peculiar that this happened to be St Vladimir’s day. Deni too thought this was an odd coincidence, given all the past associations. The liturgy at 8:30 am was beautiful, and the morning sun was streaming through the stained glass (smashed during the Reformation then patched together) of the chapel in St Michael’s. Most people had not yet arrived for the day’s events, so we had a small congregation of Mother Joanna, Niki Tait, Howard and Laurie, Dave Goode, Basil Bush, Seraphim Alton Honeywell, and Jeanne Harper. Fr Michael Harper and I served together. Deni led the choir. The Gospel reading was John 10:1-9: “I am the door, if anyone comes through me, he will be saved and will go in and out and find pasture.” Jesus is the door. This reminded me once again not to put your trust in “princes and sons of men.”

What a day. Not entirely satisfying, but there we go. The Institute is legal, and the Working Group will soon become the Board of Directors. (Well, for the moment Bishop Kallistos, Bishop Basil, and I are still the directors, pending formal ratification by the Members). I was formally appointed and given the title of “Principal.” But they took so long in the meeting to decide my fate—Deni and I were asked to wait outside during their deliberations—that I lost a lot of confidence. Not confidence, really, but I was surprised in a deflated way. Bishop Kallistos and Bishop Basil told me later the appointment itself was not in question, only the manner of appointment. In the end they agreed that Bishop Kallistos and Bishop Basil should go over my CV, interview, and tighten the principal’s job description. I am appointed for three years, subject to review after the first year. And as an employee, I suppose I won’t be able to continue as a director.

But the general tone of it all puzzles me. I felt a critical spirit. Yes, there’s much to point out as still incomplete: I haven’t finished my doctorate, and the plans for the Institute are still evolving. Some of the criticism just left me grasping for words. And I was disappointed by the lack of gratitude toward those who have been on the ground in Cambridge preparing these past two years. Fr Michael Harper too noticed this perplexing downbeat air. He’s usually so enthusiastic, but he remarked to me on the “soporific” feel of the meeting. When I spoke later with Bishop Kallistos about this, he told me he’d learned something from his nanny. “Before you say anything, ask yourself three questions:

- Is it true?

- Is it kind?

- Is it necessary?

We could use that rule to run our meetings. If something critical can be quietly said in private, do that instead. Perhaps this was just the normal temptation that assails new ventures. On the other hand, Joy Tetley has been a grace-filled presence. She told me confidentially that she will be taking a big step up as Archdeacon of Gloucester. But she wants to “covenant” to IOCS—give a monthly gift. She had to leave during the second half of the meeting but said she was praying for me all the while, and I believe it.

After the meeting, for the inaugural reception with other guests from the Federation, Bishop Kallistos celebrated the Thanksgiving Service, and I felt very keenly the words, “The stone which the builders rejected has become the cornerstone. This is the Lord’s doing and it is marvelous in our eyes” (Psalm 117/118: 22-23). I was the reader, Deni led our little choir, and it was beautiful. Bishop Basil led “Many Years” for Ivor Jones, whose last day in the CTF coincided with our first (a moving van had been outside all day).

So much to do now to get ready for the Syndesmos Assembly in Finland. Tomorrow morning, I leave on the 4 am bus for the airport.

29

Friday, February 12, 1999

Went to Fr Hilarion Alfeyev’s lecture at the Faculty of Divinity on St Isaac the Syrian (Prof David Ford had invited him to spend a term in Cambridge). Just a handful of people, but the listeners included Janet Martin Soskice, David Ford, and John Binns. I was struck by some persistent themes as he spoke. Wonder, universal salvation (after a period of purification for some). And everything for Isaac is seen in light of the most essential: God is love. The two of us went for lunch afterwards at “The Mitre Pub.” Dave Goode was sitting at the corner table, so we joined him. Fr Hilarion is being encouraged to apply for the patristics position that will be open after Lionel Wickham’s retirement this year. He is very keen. He is tired of the ecclesiastical work that could be done by others, tired of the frustration of not being able to make a more significant scholarly contribution in Russia, of being raked over the coals as a “liberal” every two weeks in the pages of Radonezh, tired of being a whipping boy for ecumenism, especially when he doesn’t see participation in the ecumenical movement as institutionally valuable for the Russian Orthodox Church. Being in Cambridge he would miss Russia, but he could always go back during holidays. And he would bring his mother with him to England. He has David Ford’s support. St Vladimir’s Seminary would welcome him he says, but he prefers a university. He’s such a natural for this. I pray that a way will be found to overcome the objections of Metropolitan Kirill [Gundyaev] of Smolensk [then head of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department of External Church Relations, and in 2009 elected Patriarch of Moscow] and bring him here.

Later I had a conversation with Demetrios Bathrellos about the Institute and his doctoral studies at King’s College London. As I was talking about our family spending a year in Thessaloniki 1994-95, I discovered that Fr Nicholas from St George’s Church in Panorama is his uncle. What a surprise it was for both of us. He was pleased to hear that we have such good memories of Fr Nicholas.

Thursday, March 11, 1999

Over the last couple of days Howard Fitzpatrick has been getting cold feet about the Institute’s projected start in October. Stewart Armour also. But this is a work of faith and has been from the beginning. We’ve never been certain about where the money would come from. They need to understand this. Faith first, then the money. Not the other way around. Gideon: God insists on less troops, not more. Moses: when did the waters of the Red Sea part for the people of Israel? According to the rabbis, when the waters were up to their nostrils.

Friday, April 30, 1999

Deni reminded me of something I need to keep in front of my eyes hourly with this Institute project: joy. “You have to figure this one out. If you get constantly overwhelmed by how much there is to do and look depressed, that won’t help anybody. You need to look like you have joy in this.” Fr Stephen Headley said something similar: “Let the cross of Christ be the way. Yes, get organized, do whatever is necessary to address the issues, but at all times, ‘Rejoice, and again I say rejoice!’ Let others sense that amid everything else at the Institute there is calm, joy, peace, delight.” The key is having the regular prayer life which doesn’t get shoved aside by other demands. And not be ruffled by the anxieties of nay-sayers.

Spoke the last hour and a half with Andrew Louth about the programme for next year. Very stimulating. The need to address core areas each year and then deepened each subsequent year. Music and art need to be included, perhaps under the broad rubric of the “Philocalic Tradition,” which would embrace everything from prayer, to asceticism, to music, to family life. Everything through which a person responds to God, through which a person’s response is molded. He immediately thought of Evagrius. “Do you know how Evagrius advised responding to anger? He thought anger was the worst temptation. All other temptations merely interfere with prayer, but anger makes prayer impossible. To overcome anger, he said we need to sing.” Evagrius had in mind singing the Psalms, but singing any soothing music dissipates not only anger, but despair and the sense of being overwhelmed. Creating and appreciating any art forces us to slow down, to keep the rushing from taking over, to be in the present. As Robert Frost says of poetry, it is “a momentary stay against confusion.” One of Fr Paul Lazor’s favorite prayers: “O Lord, let none of us who stand about Thy altar be put to confusion” (Presanctified Liturgy).

I’m on the train now to London to meet with Metropolitan Anthony and Bishop Basil.

Tuesday, May 4, 1999

Last Friday was a very long day. Bishop Basil and I met with Metropolitan Anthony, and he agreed to all our requests. He will write a letter to potential donors. We can attach his name to a fund for the Institute. He will write a general letter of support and will encourage some major donors to send their funds to the Institute rather than the Diocese. He agreed to have potential donors visit him. He even suggested that a new diocesan fund of 1500 pounds named for Patriarch Aleksy be donated in the Patriarch’s honor to the Institute. But Metropolitan Anthony still seems distant. I think the project is more than he can take an interest in right now.

But on another matter, he was more animated. I asked him about the draft of the diocesan statutes, and he thought that some of the diocesan council members ought to be appointed rather than elected. Why? “Voting ensures that the candidates most acceptable to everyone are elected. That means that a safe middle-of-the-road council is elected rather than a group that reflects the full range of views within the diocese.” I’d never thought of this before, but he’s right. Democracy of this sort flattens out the differences. Metropolitan Anthony is more revolutionary. He wants to keep voices of dissent from being silenced, and the church from being comfortable in a false sense of unanimity.

Friday, May 7, 1999

From Alex (13) this morning: he remembered that I used to bring him a cup of tea to start the day, back in New Jersey and in Thessaloniki for a bit. “But now you’re a businessman, not a father.” He wasn’t angry, just matter-of-fact. And it’s true. I get too preoccupied with everything that needs to be done to get the Institute up and running.

I was reminded yesterday that I owe a short paper for the Evangelical-Orthodox Dialogue: “What is an Orthodox Christian?” It’s supposed to be a plain basic overview, but I’m tempted to take a poetic route. I’m tired of prose religion. I want to hear of the mystery that lifts us from the cut-and-dried, the mundane, the uninspiring, the safe and risk-free. But I need time. This is what poetry requires, even if it’s in bursts. This is what Alex, Andrew, and Anthony need. And this is what our school should convey. Like Robert Frost talking with students until 3 a.m. In a world that’s always rushed, this may be the most precious witness of Orthodox Christianity.

Bishop Basil told me he’d received a letter from John Binns saying that the post of Institute Director should not be widely advertised since this gives the impression of instability. I was grateful for this. Whatever the outcome I feel better about it now. Bishop Basil will talk with Bishop Kallistos to see if Archbishop Gregorios would agree to the Working Group making an appointment.

Tuesday, May 18, 1999

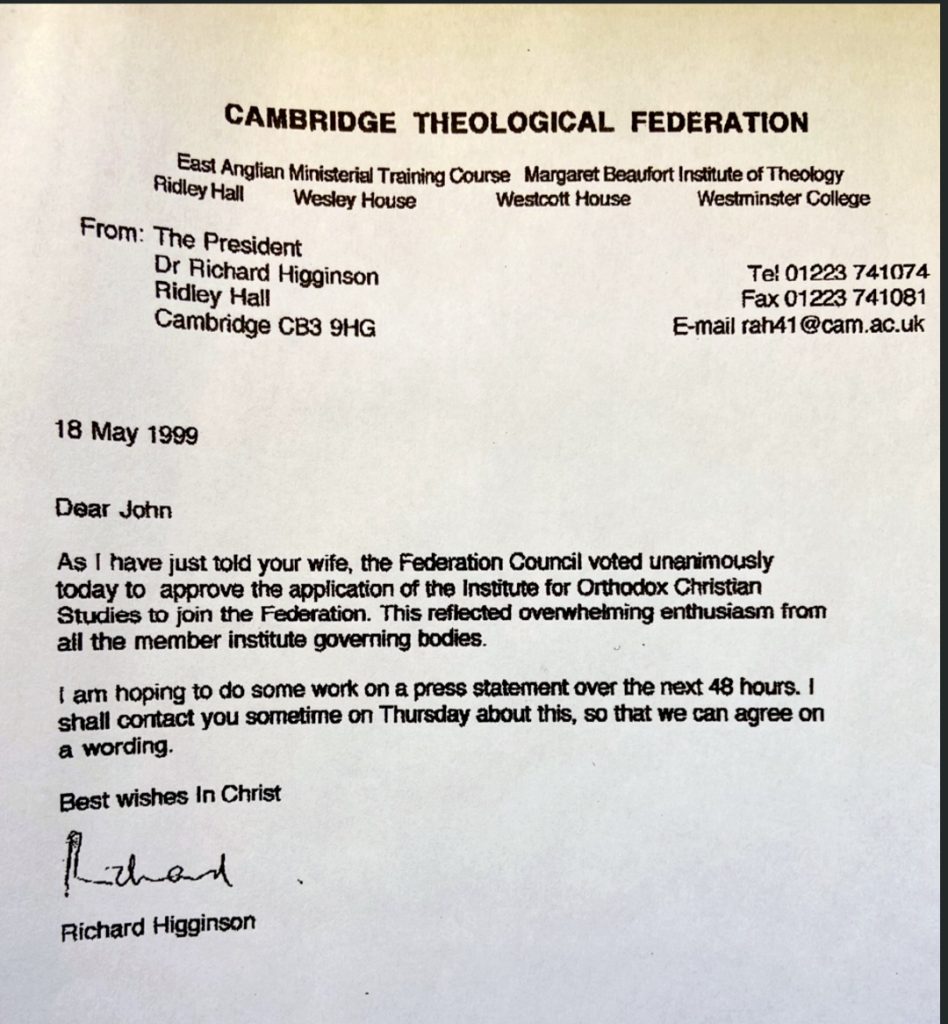

Official word from Richard Higginson (CTF president) that the Institute is accepted as a full member.

28

Tuesday, November 17, 1998

With John Binns in Oxford at the meeting of the St Alban and St Sergius Fellowship Grants Committee. It was very humbling to walk away when all was done. I didn’t speak at all except for my very brief presentation about the grant request for CISOC (6,000 pounds per year for 3 years), among many other requests. I was there as all the proposals were considered. One after another their applications were thrown out: “doesn’t fit the remit,” “could get money from elsewhere,” “too flashy,” “we don’t do PhD funding,” “we don’t fund building projects,” etc. So with only a handful of projects left to consider (the Institute was the last) it was, as I said, very humbling to get complete support, and to hear that they considered this to be one of the Fellowship’s “core projects.” I walked away very grateful. The grant they gave us represents half of the grants they give each year. As Deacon Stephen said, “Knowing how many have been turned down should be a salutary reminder to keep the Institute on the straight and narrow.” I believe this is crucial for us, not so much because of the amount, but because it gives an important signal that the Fellowship supports this new venture. This can only encourage others.

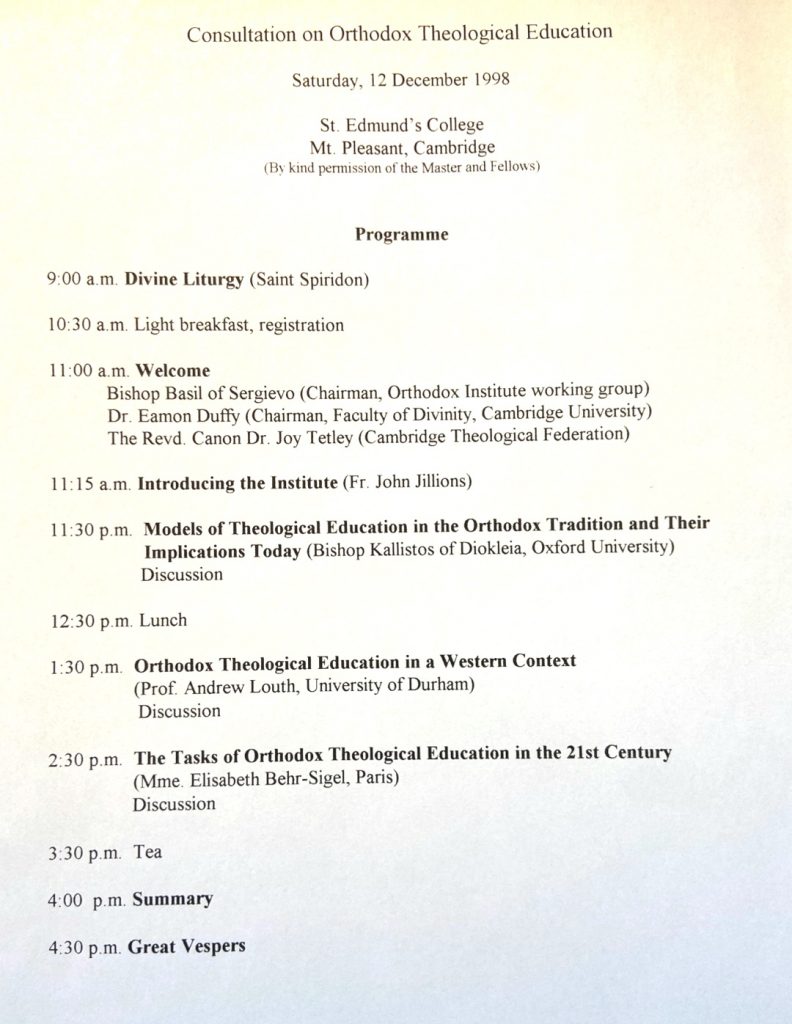

Friday, December 11, 1998

Preparing for tomorrow’s Conference at St Edmund’s College on Orthodox theology in the 21st century, with Elisabeth Behr-Sigel as keynote speaker. Life has been moving too quickly to sit down and write. My desk has returned to complete disorder, and I waste half my time just looking for lost notes on bits of paper. Now I’m at Gatwick airport waiting for Elisabeth.

I had a few minutes and opened to the next psalm in my reading, 107/108: “My heart is ready, O God…Who will guide me?… Give me help out of trouble, for vain is the help (salvation) of man…In God we shall do valiantly.” Very fitting for today and tomorrow.

[Below is the program for the consultation on Orthodox Theological Education, held in Cambridge on December 12, 1998]

Monday, December 14, 1998

I was especially struck by Bishop Kallistos’ concluding comments at the conference at St Edmund’s College with Elisabeth Behr-Sigel. He connected the theme of the conference – theological education in the 21st century—to the emergence of the new Institute.

We will have people coming to the school with many different needs and expectations and perhaps we have to be quite flexible. Perhaps once more we have to build bridges. I would like to end with one last thought, and this is my own. We spoke about the 21st century. Elisabeth offered us a profound reflection on some of the things that should guide us, but we always have to also think of this: will there in fact be a 21st century? I do not say that as a joke. I think the whole of what we do has to be open to the age to come, that we have to allow for the breaking in of eternity into time. And I think therefore that in all our planning there has to be also that eschatological element—the sense that the Last Things are always imminent. We don’t know from the point of view of time exactly how things are going to be. It may be that Antichrist is already at work in a hidden way which will be revealed. We don’t know. But I think in all our plans we ought to think also of the age to come. Everything we do is done in that context. Now those were my thoughts.

It was quite a weekend and leaves me with a sense of awe—and fear—since so much is expected, so many hopes.

Tuesday, January 26, 1999

Last Wednesday-Friday we had Metropolitan Leo of Helsinki staying with us at home. This was part of his visit to the UK to see for himself something about how ministry in the Church of England functions “on the ground.” He also wanted to learn about plans for the Institute. It was a busy week providing hospitality and accompanying the bishop.

Wednesday: meetings at Great St Mary’s; evensong at King’s College and conversation with the dean, George Pattison; dinner at our home.

Thursday: tour of King’s College, St Michael’s, Westminster College (CTF), Tyndale House and tea with Bruce Winter; lunch at “The Mitre Pub.”

Friday: Visit to homeless shelter (“Jimmy’s Night Shelter”); lunch with Fr Theonas, Fr Gregory Woolfenden, and Fr Michael Harper.

Metropolitan Leo left at 1:00 pm, then I had a meeting with the CTF. Richard Higginson (the new president) said the principals met earlier in the week and remained enthusiastic about the Institute’s application. Finances remained a concern, but they felt that membership in the CTF would help with fundraising efforts.

27

Friday, July 24, 1998

Went with John Binns yesterday to Oxford for a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Fellowship of St Alban and St Sergius, expecting a proposal for substantial support for CISOC. But I was disappointed. Maybe this will take a little longer.

John is preoccupied, tired, pressured. I too get tired of church politics and church talk and told him so. He mentioned that the Archbishop of Canterbury (George Carey) had been at his church last week for a wedding and had given an excellent sermon. “In the church,” he said, “like in a swimming pool, the most noise comes from the shallow end. Go into the deep end for more peace.”

In Oxford I went over the draft letter to Archbishop Gregorios with Bishop Kallistos and Bishop Basil and they made a few minor changes. I really like being part of a team—whether with the Fellowship, the Monastery, or with Bishop Basil.

Monday, August 17, 1998

Bishop Basil came for lunch, and Deni joined us too coming home from work. We talked about liturgical services and he agreed that if we can do it, daily vespers would be a good thing, at least during term time. Also, he was rethinking Sunday liturgy. “Perhaps you need to wear three hats,” he told me. “The Institute, rector of St Ephraim’s, and offering chapel services during the week—with the permission of Metropolitan Anthony.”

Bishop Basil and I then met with Joy Tetley about the next steps with the Cambridge Theological Federation. She walked us through the various degrees and certificates so we could better see how we might be integrated into the system and eventually offer our own courses while also teaching pieces within existing courses.

Friday, August 21, 1998

Stewart and Carolyn Armour came for dinner and vespers last night. Stewart agrees that we welcome faculty from around the world to teach. Open the doors. Besides giving us the teachers we need this offers Orthodox scholars (especially younger ones) an opportunity to teach. It also gives us the chance to offer a wider variety of courses than just “the basics,” and to explore new areas. Keep opening doors, keep throwing open the shutters. Let in the fresh air, and don’t turn inwards to protect “my precious.”

Tuesday, August 25, 1998

Fr Michael and Mariamna Fortounatto stayed with us overnight for the first time. Mariamna’s father [Michael Ivanovich Theokritoff, 1888-1969] was choir director in Wiesbaden. He lost his job when Hitler handed over control of all the Russian churches the Russian Orthodox Church in Exile. “That was 1934,” she said, “and no one yet really knew what Hitler was like.” But her father had the audacity to take Hitler to court, arguing that he had no right to usurp the legitimate church authority of Metropolitan Evlogy [Georgievsky, 1868-1946]. He lost, and when the war broke out their door was bashed in and the Gestapo arrested him. A friendly Nazi—there were many, she said—interceded for him. He was released but remained under watch. He had no church to attend for the six years of the war, and the children were sent to the German Evangelical Church. Later, while she was still a child, she experienced being shot at by British planes. “The pilots were flying close to the ground and they could see their target was a child. But it was near the end of the war, and they had a policy of terrorizing the locals to ensure total non-resistance.”

Their advice on theological education: communicate experience from teacher to student, “like a staretz and disciple.” Stress the importance of the person of the teacher, and hence the need for face-to-face contact. Fr Michael and Mariamna said that they’d had many disagreements with bishops and clergy over the years. But they keep on going. As Fr Michael told me two years ago, “At the bottom of the crisis I found Christ.” He could see things in long-term perspective, and that gave him a certain fearlessness.

Wednesday, September 9, 1998

Saw John Binns yesterday. We talked about using St Peter’s Church and the chapel in St Michael’s, for the Institute, St Ephraim’s parish, or both. He had good advice and said to let Bishop Basil and Bishop Kallistos work out the issue of serving. He said his book proposal was accepted by Cambridge University Press [An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches, 2002]. Also, Archbishop Robert Runcie called him to say he was planning to go to Mount Athos. Patriarch Bartholomew had called Archbishop Gregorios to drop everything and be Runcie’s guide on the Holy Mountain. John spoke to Archbishop Runcie about the Institute, sent him materials, and suggested he quietly encourage Archbishop Gregorios’ support over a glass of ouzo on Athos!

Wednesday, September 30, 1998

I was in Oxford yesterday to meet with Fr Stephen Platt and to pick up the iconostasis that the Fellowship was loaning to the Institute (originally from St Basil’s House in London).

It has been very busy lately. The meeting of the Working Group was on Monday. Lots of people were away, Bishop Kallistos broke his tooth. But there was still a good spirit, and we did piles of work. Took a major step in basic direction of the entire program. Go for the highest route, don’t stand apart from the University and CTF but work with them. Get students for degrees from the start. Fr Samir Gholam added a great deal. He and others felt that what we develop as our programme will take time to emerge in a process that will become clearer as we get to work. Joy Tetley was very clear that the CTF also wants us to help shape the overall mission of the CTF. Not unlike what I heard Tony Blair say yesterday to the Labour Party about the UK’s role in Europe: “We can’t be leaders if we’re not partners.”

I was disappointed that the chapel remains an issue, even after Bishop Basil and Bishop Kallistos spoke by phone and agreed to a plan to keep the chapel under the Institute rather than any one bishop. But they didn’t resolve the issue of starting services. Too many seem to feel that this will look too much like the start of a Sourozh parish, and if the pan-Orthodox approach of the Institute is to be safeguarded, then better to hold off. But I’m not sure they grasp that the families and lay people who would be part of the worshipping community are essential to the teaching role of the Institute’s chapel. How can the community life we’re trying to nurture and teach be in any sense real without that? I’m left with real people here in Cambridge who need to go to church. So, my latest thinking is just to extend St Ephraim’s, but in another location not associated with the Institute (in other words, not at St Michael’s or St Peter’s).

Tuesday, October 13, 1998

Met with deans and chaplains of the colleges for one of their regular meetings, and Bishop Simon Barrington Ward was there, from Magdalene College (now retired as Bishop of Coventry). He was glad that our little conversation had resulted in a warm meeting at the Monastery.

Lunch with Constance Babington-Smith. She was pleased to hear about CISOC. She has flashes of clarity but admits that her recent stroke has taken a toll. She was genuinely moved to have a little service of prayer in her front room. She automatically—for all her frailty—went to her knees the whole time.

In the evening, around 8:30 pm, Dave Goode, Laurie [Graham] and Howard [Fitzpatrick] came over to our house for an informal chat about the meeting this coming Saturday [October 17, 1998] at St Edmund’s College about the future of St Ephraim’s parish. They’re a big help, and it’s such a pleasure not to be doing things by myself. They stressed the importance of having a place to meet each other after Liturgy, wherever that may be. They also said it would be important to let the people (and not me) talk at the meeting on Saturday. Our meeting didn’t end until just before 11 pm. And in the meantime, we have been neglectful parents: the kids begged to watch TV and we let them. It seemed like an awful movie they had on upstairs, but we didn’t have the will to fight with them. So, there we were downstairs, the adults, praying, establishing a parish, and there they were above us watching “Die Hard.”

Thursday, October 22, 1998

Last Saturday after liturgy at St Edmund’s College we had the parish meeting to discuss starting regular services. Mixed reactions. Some wanted to leave the Saturday schedule as it is, so that those who have Sunday commitments elsewhere (either Anglican or Orthodox—such as at the Sourozh Cathedral in London) could keep going to both. Others were very much in favor. I spoke about developments with the Institute and possibilities of using St Peter’s Church or St Michael’s. And continuing to use our living room as a house church on Sundays for the time being.

Monday, October 26, 1998

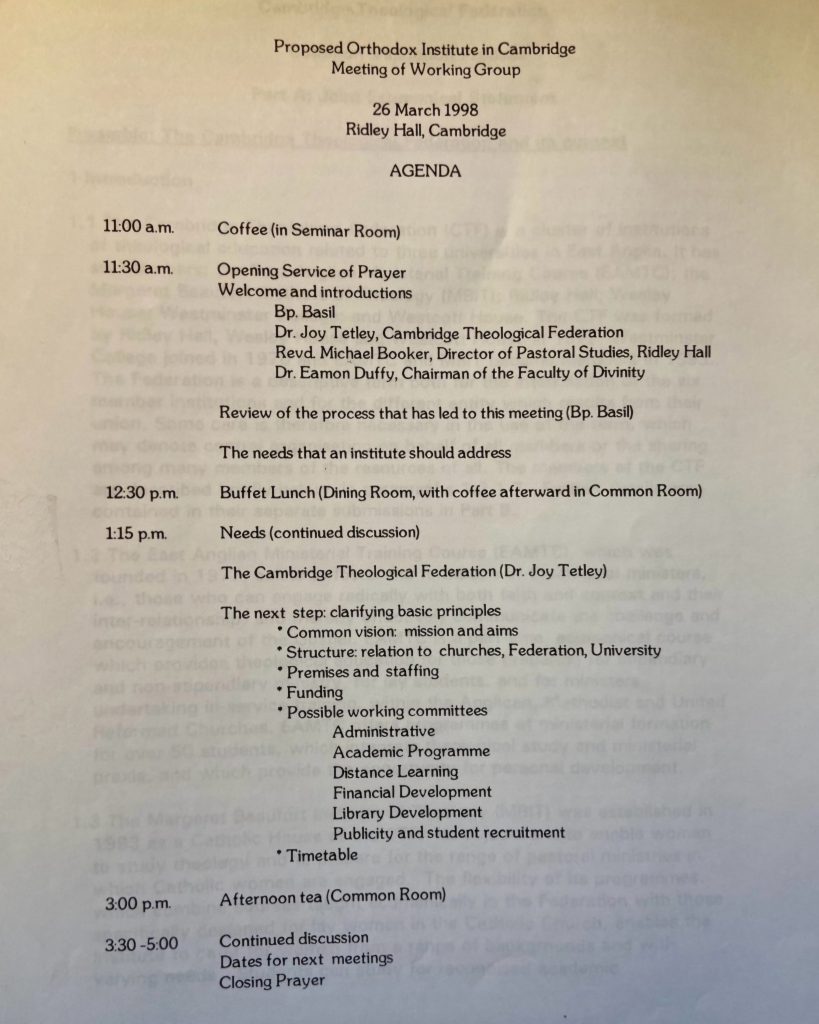

The first meeting of the CISOC/CTF “working party” was held at Ridley Hall and it went well. The Orthodox members met for coffee afterwards at “The Granta.”

26

Wednesday July 15, 1998

It’s about 8 pm, looking out the window from a hostel in Exford where I’m staying with the boys after driving through Exmor and stopping by Stonehenge. Deni is at home resting (I hope) after the big meeting on Monday (13 July). The Working Group met at Westminster College. It was a beautiful day, broken by violent storms around noon and clearing in time for dinner. We met at the big round table in the “Senatus.” Seraphim Alton Honeywell was there as legal counsel to present the governing documents. Andrew Louth had prepared materials for discussion of theological education. Bishop Kallistos was in fine form. He reported on developments with the Greek seminary. But for the first time he said that he would need the blessing of the archbishop to continue with our Cambridge Working Group since developments are becoming more concrete.

We had a surprisingly long discussion about the appropriateness of having liturgical services, especially on Sundays. I didn’t expect this, since I thought it was obvious that liturgical life should be woven into the program. But the tide was definitely in favor of patience, given the potential for misunderstanding. It needs to be clear that we are not setting up a parish. But I felt—rightly or wrongly—that the hope we’d had for integrating services into the life of the Institute was slipping away. There is currently no regular Orthodox parish life in English in Cambridge. I protested that I and my familyalso need to be ministered to, and we need a place to go to church regularly. St Ephraim’s meets only once a month on a Saturday. I bristled at the idea that an all-Greek parish “is fine,” and that an Institute chapel will be viewed as competition. How absurd. At any rate, I seemed to be alone on this. Someone—I don’t know who—said, “We know your capacity for endurance, Fr John.” But Deni and the children? All is in God’s hands.

Thursday, July 23, 1998

I woke this morning to blue skies, the sun just dawning at 5:00 am, and prepared to leave for the Monastery in Essex with the thought, “a day of many blessings.” And it has been that. I’ve been there and back. It’s only 2:00 pm, and in a little while I’ll go on my bike to meet the boys at school. But I wanted to get down some of those monastery impressions.

I wish I’d had a camera as I was leaving the monastery and pulled out of the parking lot. Fr Simeon, Fr Kyrill, Fr Silouan, and Fr Zachariah were smiling, waving goodbye in their long beards and black cassocks and hats. Such warmth, a collective “yes” to all that’s being done here in Cambridge. The way had clearly been prepared by Prof Karavidopoulos and others who had spoken well of the project. I left with a deep sense of blessing, and then saw a nun walking along the road back toward the monastery. She was still a long way off, so I turned around and offered her a lift. Sister Seraphima, from Moscow. She had just completed the St Serge correspondence course and agreed to sit with me on one of the long benches to tell me her impressions. All but Fr Zachariah were still standing in the parking lot talking about our earlier conversation. After an hour of helpful conversation with Sr Seraphima, I only then realized that she is Anya Platt’s sister, about whom I’d heard from Fr Stephen Platt. I was struck by her balance and openness. I liked especially her phrase, “We can maintain our integrity without having to maintain our ignorance.” Fear of books and other people (“the non-Orthodox and the West”) must be combatted.

But to return to the early morning. I made it to the monastery around 7:30 am, in time for the last half-hour of the morning service. Stepping into the nave it was pitch black except for the faintest lampadas in front of the main icons. I felt my way very gingerly hoping not to step on anyone. A nun was just finishing the Jesus Prayer in Slavonic and then started again in French: “Seigneur, Jésus Christ, Fils de Dieu, aie pitié de nous.” It took a few moments to find the rhythm of the prayer—about as long as it took for my eyes to adapt to the church and settle down. And then the chandelier light very, very dimly came on as the Great Doxology began in Greek, mostly with women’s voices. It was so penetrating. No, that sounds harsh, and this was gentle, yet firm. The service came to an end with “Krestu tvoemu” (“Before Thy Cross,” sung three times in Slavonic). I went outside into the sunlight and was immediately greeted by Fr Zachariah who led me into the refectory where I met the others, including Bishop Simon Barrington Ward of Coventry, there on retreat for ten days. Fr Zachariah had just returned from Thessaloniki, where he defended his doctoral dissertation.

After breakfast Fr Kyrill, Fr Simeon, Fr Zachariah, and Fr Silouan took me to the study, and we sat around the table—but Fr Sophrony’s chair was left empty. The huge mural of the Mother of God which he had painted looked down on us. As we talked, I felt such a spirit of warmth, of embracing, of balance that stays with me. “Whatever is true…” [Phil 4:8]. There’s a willingness to bless all that is good. And there’s none of that terrible “fear where there is no fear” [Psalm 53:5, cf. 1 John 4:18]. I feel that we are on the same wavelength, we and the Working Group, and the paper written by Andrew Louth. Theological education and formation without fragmentation. Enable students to “stand on their own two feet.”

Fr Simeon began with two thoughts. They later joked about Albert Einstein who was once asked, “How do you keep all your ideas in your head?” He replied: “It’s easy, I have only one idea.” That was like the monastic single-mindedness of the Jesus Prayer. But Fr Simeon had two thoughts.

- Keep the curriculum broad. Don’t specialize too quickly but enable students to foster the full range of the Church’s life and thought through a broad curriculum.

- Put liturgical life at the center, not just of worship, but as the source of theology. Liturgy as the mysticism of the Church’s thinking, of patristic thought. Get away from mere liturgical history or even patristic commentary on liturgy, and instead see liturgy as the source of theological reflection. I’ve been thinking of this for several years, so I was grateful to hear Fr Simeon put this so succinctly.

Fr Silouan was especially keen to get away from the “strange” atmosphere of western theological colleges, where clericalism and professionalism combine to form a kind of “superior” Christian with subtle disdain for the Church and the holy, forgetting that “we are sinners.” What kind of pastor can be produced by such a system?

They didn’t think ecumenical education was a frightening prospect, though perhaps shared worship should be kept as optional. Indeed, people are more important than the programme. If good people are involved even a bad programme will bear good fruit (but not vice versa).

25

Wednesday, July 8, 1998. Kazan Icon of the Mother of God.

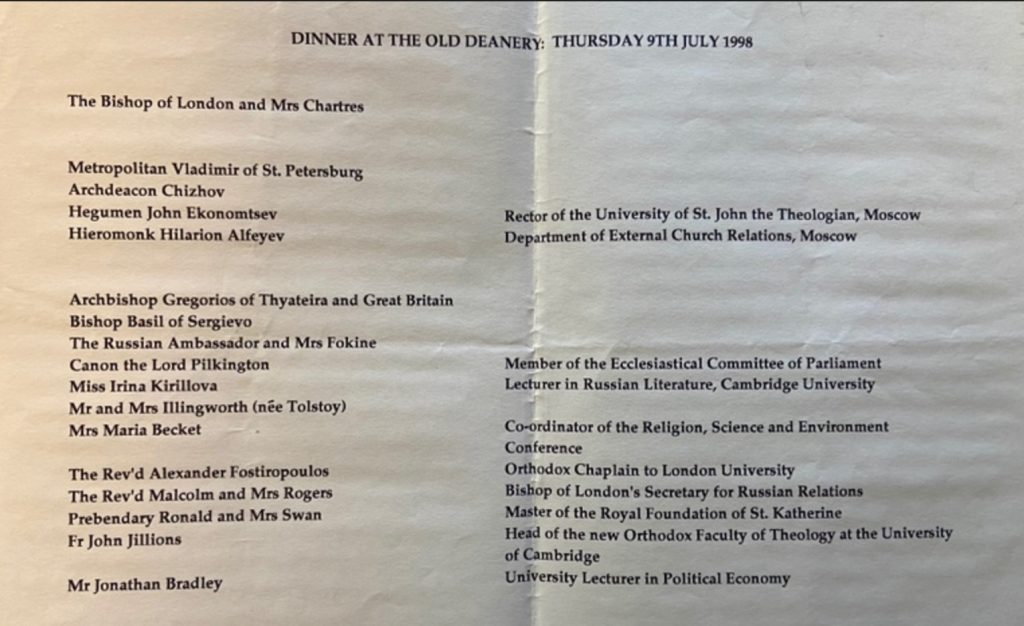

Drove boys to school and Deni to work yesterday morning and then stopped in at Great St Mary’s for morning prayers and to see John Binns. (The bells didn’t ring for some reason, so we sat for an unusually long time in silence: very helpful, that silence, for slowing down.) He says it’s OK for us to start using the chapel in St Michael’s for regular services starting on the weekend of 5-6 September. Deni took a message yesterday: I’m invited to a reception at the home of Bishop Richard Chartres, the Bishop of London—he’s aware of the Institute—with Bp Basil, Fr Hilarion (Alfeyev), Fr Economstev, and others. I also had a letter of support for the Institute from Colin Davey of the Council of Churches. The ball is rolling faster and faster. Keep holding on to be a servant of Christ. The 15,000 pounds anonymous gift for IOCS is coming in mid-July.

Friday, July 10, 1998

I went to London for the unveiling of the ten 20th century martyrs’ statues on the façade of Westminster Abbey and then dinner at the home of the Bishop of London, Richard Chartres. Well, it wasn’t the unveiling itself by the Queen, which was by invitation, but I went to evensong at the end of the day and bought the commemorative book. But perhaps that simple evensong was just as meaningful, maybe more so, without the hoopla, to just consider those 10 lives of people who stood up for Christ. Including our own St Elizabeth the Grand Duchess and New Martyr [the remains of Princess Alice—Prince Philip’s mother—lie alongside the remains of St Elizabeth in the chapel of the Russian Orthodox convent in Jerusalem].

- Maximilian Kolbe (1894-1941)

- Manche Masemola (ca 1913-1928)

- Archbishop Janani Luwum (ca 1922-1977)

- Grand Duchess Elizabeth (1864-1918)

- Martin Luther King (1929-1968)

- Óscar Romero (1917-1980)

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945)

- Esther John (1929-1960)

- Lucian Tapiedi (1921-1942)

- Wang Zhiming (1907-1973)

The readings at evensong were especially poignant for me. Exodus 14:14: “The Lord will fight for you; you need only to be still.” 1 Cor 15:58: “In the Lord, your labour is not in vain.”

I was discouraged and needed this. Fr Theonas called yesterday to say the archbishop had phoned to tell him to take his name off the list of IOCS bank signatories. Fr Theonas was upset but resigned. He wondered, “why this opposition to doing good?” I keep hearing too (from Stewart, Elizabeth and George, Fr Michael Harper) that Fr Ephrem Lash is constantly speaking against the project. So, the beauty of Evensong, the example of the martyrs, and these readings left me feeling uplifted and refocused. I’m getting anti-institutional, or rather, it’s the focus on Christ that is more and more important to me, and I am increasingly impatient with the gap between revelation and reality in the life of the Orthodox Church. For example, John Binns just returned from Mt Athos. He was well-received at St Paul monastery, but at a little Greek monastery where he had to stay because the better-known ones were full, being an Anglican priest he wasn’t allowed to stand in church for vespers, and—to the dismay of the Greek pilgrims there—he wasn’t even allowed to eat with the Orthodox guests.

I arrived early at St Paul’s Cathedral for the dinner with the Bishop of London, and found Bishop Basil sitting on a bench in the cathedral grounds reading a book—The Joy of Being Wrong (James Allison). As Deni said later, Bishop Basil is a genuine intellectual, one who delights—that’s the best word, delights—in thought, making connections from one field to another, considering implications. The message of this book is that God identifies with the outcast, because he is the scapegoat, the one expelled by the powerful. This makes him and his followers—the martyrs I saw today—revolutionary and subversive of all human culture. The Romans saw this and recognized the threat.

We walked to the Dean’s Court around the side of St Paul’s and found the unmarked Old Deanery. The Deans used to live there but now it’s the home of the Bishop of London. Bishop Chartres opened the door, greeted us, and we were quickly followed by most of the other guests. Metropolitan Vladimir of St Petersburgh, Archbishop Gregorios, Ambassador Fokine, Fr John Ekonomtsev, Irina Kirillova, Fr Hilarion Alfeyev (I sat next to him), Fr Alex Fostiropoulos, and others.

At coffee I spoke with Archbishop Gregorios. He is unfailingly charming. I asked him directly about Fr Theonas, saying I knew the archbishop had certain objections. And I said too that I’d heard of Fr Ephrem’s objections. He said yes, he had originally given his blessing for exploration. But now it seems that actions are being taken. I reiterated the need to have the people involved keep meeting. He agreed but did not get too specific, though he did say he would be sending a letter asking for clarification. He still insisted that his interest is in whatever is good for the whole church. And he agreed that given the small pool of people we’re dealing with in the UK, it would be good to work together and not in conflict. We should be able to divide the work so there’s not too much overlap. In fact, I could foresee several sites in the UK working under one umbrella. I also thought that others would support us if they saw us working together on a joint effort.

The archbishop had been sitting next to Bishop Chartres during the dinner, in close conversation. I wondered if he was saying much about his seminary plans. But Bishop Basil is sure we have a friend in the Bishop of London, who was very encouraging to him and to me about Cambridge. When Bishop Basil hinted obliquely at the “inter-Orthodox situation,” Bishop Chartres just smiled. He knows what goes on.

Bishop Basil called last night to find out how my conversation with Archbshop Gregorios had gone since he had to leave while I was talking with the archbishop. He’s sure we need to just keep at it. I recalled Bishop Kallistos saying we should not just set up a “shell,” but should get into teaching and serving ASAP. I can see that this organizational stuff could become a preoccupation with “the shell,” while shunting real students into the background as we play these games. So, keep the focus on the students, on serving, on actions, on CHRIST. The rest can stamp their feet, and huff and puff, but let the building go on. Get the distance learning underway. Put efforts into Cambridge, building a solid presence in the University and the CTF. Have more conversations here, in Cambridge. We need the local base of strength from which to work. Then the other conversations will follow. The “political issues” are classic temptations thrown into the road to keep us from making progress. As Bishop Basil said, “talk alone will just kill the whole thing.” We keep moving, keep including, keep inviting participation, but stay focused on the real needs and real people who will not be served if we just dither.

Regarding Fr Ephrem: Bishop Basil felt it best if others deal with him, rather than me trying to go head-to-head with him. That’s probably wise, given his passionate pen! Take the high road with him. What about inviting Metropolitan John Zizioulas to Monday’s meeting, as Fr Hilarion had suggested? Bishop Basil said, “If it could be just a cup of coffee and conversation you might get something out of him, but the meeting is sufficiently formal that he will be unable to contribute primarily as theologian. Instead, his role as loyal son of Constantinople will dominate.” And Bishop Basil mentioned an interesting fact: Metropolitan John never serves anywhere in the UK except the Monastery of St John the Baptist, because it’s directly under the Ecumenical Patriarch.

24

Wednesday, June 3, 1998

Last Sunday Metropolitan Anthony was serving at the Cathedral. I didn’t expect to see him since he’s been out of communication lately and the Sourozh conference last week was a rare foray. But he had given an amazing talk and I wanted him to know how much I appreciated it. Especially his image of the walled garden. He had spoken about his youth and conversion, and how he faced a choice. “Do I to keep this precious faith to myself, like a walled garden, or do I break down the walls and share it with others?” This analogy became a theme throughout the conference, with reflection on the need to first build a walled garden to grow for a time, but then to open up to others. He told me how terrifying it was at first to speak in the first person about his own experience. He wanted me to tell Deni how much he appreciated her organization of the Conference, admitting that he was a poor correspondent (“as you know”). We agreed to meet again with Bishop Basil to talk about the next steps with the Institute.

As always, his celebration of the Liturgy is one of utter peace in the presence of God. There is not a note of anxiety or grandstanding or public display. As Kelsey [Cheshire] said to me later (she is extraordinarily—and disconcertingly—intuitive), “he used to [she put it in the past] carry the Liturgy with him into the congregation, after it was over, and he’d sit down on a bench in the nave while people would come up to him and bring their concerns. I had the impression of his carrying a light, or being enfolded in light, as a peace that went with him, much like the very first time I saw him at the entrance during the pontifical liturgy during the feast of All Saints.” I’ve heard there is a cranky side to him lately, and he’s difficult with the administration of the cathedral, but I am far removed from that and I can’t forget his celebration of the liturgy.

Thursday, June 4, 1998

I’m again in the little French coffee shop across the street from the Royal Bank of Scotland, about to put in the first deposit for the Institute, checks from Holy Transfiguration parish in Walsingham, and Fr Philip and Philippa Steer.

Thursday, July 2, 1998. Wells Next-the-Sea, Norfolk.

[Rewarded myself for finishing my PhD dissertation by taking a train and bike excursion to King’s Lynn and then Wells].

The biking was harder than I expected. Every little rise began to take its toll. But the countryside was beautiful. Sandringham, Dersingham, Sherbourne, Docking, Burnham Market. I stopped there for a half-pint of Norfolk bitter and cherry pie at a 17th c. hotel, “the best pub, 1996.” Then made the rest of the five miles to Wells, to stay overnight with the Armours. It was just Stewart and Nicholas since Carolyn was in Barbados at a family reunion. I was not feeling very sparkly and needed a rest. But Stewart had some good advice about the Institute:

- Be cautious about how we integrate the Orthodox and non-Orthodox dimensions of the education, look at it as an experiment. See how it can be worked out in practice. Try it. Don’t be frightened off in advance. Anything we do will be criticized, so it’s best to just seek to do good. God’s will. Remember that the Orthodox students will have a chance to debrief about their non-Orthodox teaching/experiences. And they will have the Orthodox services to participate in to help shape them. We as Orthodox may be able to help the CTF as well.

- Success with fundraising at SVS had brought a different spirit: “Be careful.”

- Don’t be discouraged by the small beginning. The Cambridge project is needed: stay focused on that and on the real people it will serve.

I have to say that I’m very tired of “Orthodox talk” or even “church talk” of any kind. It’s all so disconnected from life. “God is the interesting thing” (Evelynn Underhill). And so with the Institute: keep communion with God as the focus of prayer, study and worship. All of this is to make communion and service in his name possible. If we keep God at the center of our work, we won’t need to afraid of the “non-Orthodox”.

Saturday, July 4, 1998

Yesterday was the next meeting of the Working Group in London at the Sourozh cathedral. Must keep going despite the archbishop’s attempts to start something as well (he even called Fr Samir Gholam!). Fr Ephrem is getting fairly exercised about this—according to Andrew Louth and Elizabeth Theokritoff. He thinks that the archbishop’s project won’t get off the ground if the Cambridge project goes ahead, but I think Fr Ephrem underestimates the archbishop’s resolve. I asked at lunch whether we should just offer the entire Cambridge project to Archbishop Gregorios and ask him to be the chair. Bishop Basil didn’t see this as a bad idea, but like the SCOBA model in the USA thought the chair should still be elected. It shouldn’t automatically go to the EP representative. But as Andrew Louth said, the one thing the archbishop’s seminary task force had agreed on was that the location should be London. So, we keep going, and these concerns were barely touched upon until lunch. We spent two hours in the morning speaking seriously and fruitfully about the basic principles that should guide the Institute, using Andrew Louth’s short paper as a jumping off point. We agreed that personal formation must be at the root of the education. This would enable students who go through the course to stand on their own two feet, giving them the resources to do so, knowing that they will not be going into situations where they will have ready-made church life. They will have to be the church in that place as missionaries and witnesses. As Bishop Basil pointed out, the very first place they could learn this is in the CTF, where they will be with others, challenged, questioned. We agreed that while giving an Orthodox formation we need not be afraid of others. Indeed, in this Orthodox formation, if we give students the sense that the weight of the whole church is behind them—the communion of saints, and God himself (hence Andrew Louth’s emphasis on the Philokalia)—then this experience of the church will enable them to discern what’s best elsewhere and to “despoil the Egyptians.”

We agreed to invite the Monastery of St John the Baptist to send a representative to the next meeting (they were keen to be involved according to reports), and to hold two conferences. The first to bring together Orthodox from around the UK. And the second to bring in Orthodox from around the world with expertise in theological education (like John Behr, John Chryssavgis, and others).

23

Saturday, May 30, 1998

Deni and I had an important conversation with George and Elizabeth Theokritoff about the Institute’s general approach. We agreed that there needs to be a balance between passive absorption of healthy Orthodox teaching in an environment and by teachers that can be trusted (like SVS), and the development of critical thinking and the skill of discernment in an environment that keeps challenging assumptions (like Cambridge-Oxford). The first priority is to nurture and cocoon our students and give them the basics in a healthy Orthodox “home.” But then there needs to be an “un-cocooning,” not unlike what Fr Florovsky did early on at St Vladimir’s by bringing in speakers from the wider world. The students need to be stirred, to realize that other peoples’ convictions are not as ridiculous or as easily dismissed as they may seem on paper or in a class of like-minded Orthodox. The Institute needs to:

- provide solid Orthodox teaching

- enable students to examine their own assumptions, often brought in from their non-Orthodox past and still at work, but without dismissing everything from their past as bad or “non-Orthodox”

- discern true from false in whatever they receive elsewhere, whether that’s the Theological Federation or the culture at large.

We agreed that studying with others who do not share all their Orthodox assumptions could be the humbling element that keeps the academic programme from producing graduates who think they have all the answers. The aim is to help them grow as followers of Christ, with Christ being the criterion of truth (John 14:10-21, as I read today). Our part is to keep Christ’s words and follow his commandments. And then Christ will do his part: he will ask the Father to send us the Spirit of truth to reveal himself: “If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you for ever, even the Spirit of truth” ( John 14:15-17; cf. Rev 3:20).

Tuesday, June 2, 1998

Today I will meet for the first time with the CTF Executive. In today’s readings Paul is violently pressed by the crowd (Acts 21:26-32) and Jesus warns the disciples that “the time is coming when everyone who kills you will think he is offering worship to God” (John 16:2-13). This is even more meaningful given the message Deni received from Jim Forest’s email group that there was a public burning in Ekaterinburg of books by Fr Alexander Schmemann, Fr John Meyendorff, and Fr Alexander Men. The local bishop ordered their books to be removed from the ecclesiastical school and burned, without comment. The priests who were “sympathizers” of these banned writers were turned in and told to recant. Two did, but one refused and is now deposed. I was told that a TV programme in Kosovo featured Serbian Orthodox priests blessing the meetings of nationalists and leading hostile protest marches through Muslim districts. There is a collision course for the Orthodox. We just need to stay faithful to the truth, the spirit of truth who guides us (John 16:13).

***

I continue this now at 3:50 in the afternoon, just having returned from a meeting at Wesley House with the CTF Executive Committee. There was interest and encouragement, but also British reserve. It lacked the sparkle I’m used to with the Working Group. John Proctor, the Federation president (from Westminster College), has always been warm with me, but I can see that he needs to be much more reserved when obliged to go over the “fine print” of the conditions and obligations of our potential membership in the Federation. He was at pains that we not “feel hustled” (his words). The CTF wants to take all the right steps, “but on the other hand we don’t want to delay the process unnecessarily either.” The questions they put to me, and my answers:

- How can the Federation help us? (Familiarize us with the CTF, give practical advice)

- What do we foresee as the stumbling blocks? (Keeping it pan-Orthodox, pulling the administration and funding together, preparing an Orthodox/ecumenical academic programme)

- Where are Orthodox (especially clergy) now being trained in the UK? (Outside the country or by the local bishop)

- Are there any Roman Catholics on the Working Group? Would we be willing to work with Roman Catholics, especially given the Pope’s hope for union with the Orthodox? But they are conscious of the “sensitivity” of this issue. (I didn’t see this as a problem).

- When should they appoint a 2-3 person “negotiating team” for the CTF? I felt we should wait until the next meeting of the CTF Exec, and at least until our legal status is clear and we have a better sense of our own identity and academic programme. I also felt the need—even more—for a permanent representative from the University of Cambridge Faculty of Divinity. Although I didn’t say this baldly, I felt that without this the Institute might be in danger of being sidelined from the main theological conversations to which Orthodox might contribute.

22

Wednesday, May 20, 1998

There is so much to write about yesterday’s meeting of the Working Group. Remarkable people, remarkable day. There’s a lifetime’s worth of reflection here on what’s happening. But I have very little time now. It’s almost 7 am and I’ll need to get everyone up (Fr Sergei Hackel is sleeping in the living room). “You have only to be still” was borne out. I worked very hard before the meeting and felt hopelessly disorganized—no plan—still writing it up early yesterday morning. Felt very confused. Deni helped set it out quickly: she’s so clear-thinking. But after that there was little to do except go to the meeting and see what unfolded. God is faithful but I keep needing reassurance.

The boys were at the margins of all this later at dinner, but I think they enjoyed the hoopla in our back yard. As Bishop Kallistos was leaving Anthony was handing out chocolates, and the bishop said, “One for the road!” as he took another gold-wrapped Ferrero Rocher. Alex said later that the bishop immediately unwrapped the chocolate and ate it then and there. “Huh—’One for the road!’ He’s cool.”

Thursday May 21, 1998

I’m still catching up on the Working Group meeting earlier this week, sitting in a coffee shop across the street from the Royal Bank of Scotland. Fr Theonas and I will go there tomorrow to open the Institute’s account (it’s pan-Orthodox, with me, Fr Theonas and Fr Michael Harper as signatories—MP, EP and AP). But today I want to make sure of the arrangements and also to deposit into our personal account the much needed cheque from the EAMTC weekend. Then home again to keep following up on the Working Group meeting before we all leave for Oxford and the Sourozh Diocesan Conference on Friday afternoon.

The week began (Mon. May 18) with dinner with Fr John Breck and the group from Paris (plus Jeanne Knights), whom I then deposited at “Antonio’s Guest House.” I came home around 11 pm to put the last touches on preparations for the meeting (somewhere in there I picked up Deni from work, and Anthony from his piano lesson and brought them home). I still had the agenda to finalize and had to come up with a draft “Plan and Timetable,” including a budget, job description for the Institute director, and an outline for the initial phase of the project. I sat there at the computer, surrounded by papers lying everywhere, music CDs the kids had been playing, mail, and a general mess. The CISOC papers were jumbled together in a box, mixed in with other bits of information. At first, I couldn’t even find the planning notes I’d written for the last meeting. I felt confused, in a daze, numb, with no handle on the direction except for the brief conversation I’d had with Deni two nights earlier, in which she had laid out so clearly the pieces to include. I felt, in retrospect, like I did before the physics final exam at McGill in 1974: I was trying to memorize formulas, but couldn’t grasp the whole picture. The one thing I knew was that we need a draft plan. Even getting up at 5 am didn’t help and I wasn’t getting anywhere. But after talking it through with Deni I finally got something down on paper and felt better. The image of Gideon kept coming back to me, and the thought, “You have only to be still.” Trust that God is at work in the hearts of others.

Deni was off that day, so while she took the kids to school (Andrew rode his bike and wouldn’t be home till late, after the “talent night” concert at school) I rode my bike to Staples to make last minute copies of the agenda, and then up to the guest house to meet Fr John Breck et al. By then, by God’s grace, I was ready to enjoy the day. That thought too keeps coming to me at stressful moments like this: “Enjoy it!” It was one of those glorious Cambridge mornings as we were walking down Castle Street, past St Peter’s and through the town on our way to meet Albert Lavigne, the French cultural attaché who was joining us because of the St Serge-Paris connection. We stopped at Great St Mary’s, bought a few souvenirs for the Parisians, and saw John Binns, who was just finishing morning prayers. I’ll continue this later. But for now, I want to remember that I woke up with the recurring thought of a motto for the Institute: “Welcome one another (accept one another) as Christ has welcomed you” (Rom 15:7).

Wednesday, May 27, 1998

I still have not caught up with the events of last week—the meeting on the 19th with the Working Group, the Sourozh conference in Oxford—but there’s too much going on. The boys are home from school on midterm break, Deni’s off to work, and we still have our suitcases from the conference sitting in the kitchen. There are papers, bills, mail in every room, and loose ends everywhere. But yesterday I went to the men’s group at Tyndale House and—although it’s hard for me to ask—I asked them to pray about the financial needs for my family and the new Institute. A few hours later I was talking with Bishop Basil. He told me that A and B were giving 10,000 pounds to the Institute. “O Lord, how manifold are thy works…!” Each time something like this happens I just shake my head. As Stewart Armour is fond of saying with his wry sense of humor, “It’s enough to make you believe!”

Thursday, May 28, 1998

I still haven’t written much about the Working Group meeting on May 19th but must try before the details fade.

We met at the offices of the EAMTC and everyone was there except Fr Ephrem Lash. Again, the highlight was the collaboration of Bishop Basil and Bishop Kallistos. Especially Bishop Kallistos’ handling of the governing documents. For more than an hour he went through the draft section by section. I saw Deni looking at him with such delight, smiling, her note-taking suspended. And I felt the same way. He is making this his own. My meeting with Archbishop Gregorios had obviously provoked him to get moving on his own project.

It was very funny. After I reported on my meeting with Archbishop Gregorios, Bishop Kallistos smiled, piped up and said, “As a matter of fact, the archbishop also called me…” It turned out that the archbishop had also called Fr Christos Christakis, and then Andrew Louth. It was all in such good humor. We agreed that we need to move together on this. Fr Christos was less optimistic about the archbishop’s intentions, his willingness to collaborate, and its impact on us. Elizabeth Theokritoff was also less willing to be so sympathetic to the archbishop and was very upset by the tendency she’s seen before. “If there’s something good, then they have to have their own.” At any rate, I’ve written to Archbishop Gregorios, and we hope he’ll agree to have his planning group meet with us so that we can then somehow coordinate our development.